UPDATE: For folks who want a little more guidance in terms of specific microphones, I did a follow-up post that you might find interesting. Original post follows.

Taking a brief break from my usual diet of code for some fun with audio gear…

Why Podcast/Screencast?

Podcasting and screencasting are two very effective ways of communicating information. A blog post or technical article can provide much deeper detail in many cases, but a podcast or screencast provides the human element that can often maintain a listener’s (or viewer’s) interest long enough to get the point across, while some recent data have demonstrated that most people rarely make it to the end of an online article.

The Importance of Audio

When creating podcasts, audio is clearly a critical element. If your listeners can’t understand you, or if there are distracting noises in the background, it will be difficult to get your listeners to come back to your podcast more than once, and they may not even finish listening to a given episode.

When creating podcasts, audio is clearly a critical element. If your listeners can’t understand you, or if there are distracting noises in the background, it will be difficult to get your listeners to come back to your podcast more than once, and they may not even finish listening to a given episode.

But audio is sometimes overlooked when creating screencasts, or videos, for a variety of reasons, particularly among folks who don’t record regularly. This may include not having a good microphone or headset available, or just not knowing how poor the audio quality of a built-in laptop microphone can be. The short version of my argument is that low audio quality can cost you your audience. And since they’re kinda the point of what you’re doing in the first place, it’s good to get audio equipment that will make you sound your best.

There are many degrees of quality when it comes to potential gear for recording, and it doesn’t have to cost you a fortune to improve upon the quality of a built-in laptop microphone.

Options to Consider

First off, you can get a USB headset. These vary in price and quality, and when you plug them in, they essentially act as an external sound card, with the microphone and speakers built into the headset. Note that depending on what software you are using to record your audio (whether just audio alone, or along with video or what’s on screen for a screencast), you may need to configure the audio options of that software to use your headset as the input and output source. I used to use a reasonably-priced Logitech headset for audio, but while it’s plenty good for conference calls, I didn’t find it terribly comfortable for long use, and eventually the foam on the earpads deteriorated, and I haven’t bothered replacing the unit. If you can, look for a headset with noise cancelling technology, as that may help eliminate distracting noises from your environment.

Another headset option is Bluetooth, but while I’m a fan of these headsets for conference calls, because I’m not tethered to my laptop and can get up and move around, Bluetooth adds another level of potential issues in terms of both drivers and interference. For that reason, I don’t use my BT headset for recording podcasts or screencasts.

The best option, IMO, is a good quality external microphone. There are two ways you can go here. First, you can use a standard audio mic, which typically uses a 3-pin XLR connector (some microphones use 1/4″ audio jacks…I don’t recommend using these, as they are typically lower quality). An advantage with using a standard audio mic is that you will have a very wide range of prices and styles to choose from, and depending on your other hobbies (for example, if you’re also a musician), you may be able to save some money by reusing the same mic for both your musical endeavors and for your recording needs. There are many factors that go into choosing a good standard audio mic, and they go well beyond the scope of this post. If you go this route, you will also need some form of adapter or external sound card that will convert the analog signal from the XLR connector to a digital signal that your computer can make use of.

The best option, IMO, is a good quality external microphone. There are two ways you can go here. First, you can use a standard audio mic, which typically uses a 3-pin XLR connector (some microphones use 1/4″ audio jacks…I don’t recommend using these, as they are typically lower quality). An advantage with using a standard audio mic is that you will have a very wide range of prices and styles to choose from, and depending on your other hobbies (for example, if you’re also a musician), you may be able to save some money by reusing the same mic for both your musical endeavors and for your recording needs. There are many factors that go into choosing a good standard audio mic, and they go well beyond the scope of this post. If you go this route, you will also need some form of adapter or external sound card that will convert the analog signal from the XLR connector to a digital signal that your computer can make use of.

Given the added expense and complexity of needing an adapter, I’ve chosen to go the second route by using a microphone that connects to my laptop via USB. As with the headset, the microphone acts as its own sound card, and each piece of audio recording software needs to be configured to use that input as its audio source. Although not as many as standard audio mics, there are many choices available for USB microphones, at pretty much every price range.

My recommendation is to find a condenser model that fits your budget. Condenser mics can often provide better quality because they use active electronics, rather than passive magnetic coils, to produce the audio signal. Of course, like anything you read about audio, there are those who disagree, and find dynamic mics preferable. This is one of those areas where your ears should be your guide…if you have the opportunity, borrow a friend’s mic, or see if you can test out mics at a local electronics or musical instrument shop, to see which you prefer. If you’re going with USB, the vast majority of these mics are condenser, so that’s what you’ll likely end up with.

One important thing when choosing a USB mic (or headset, for that matter) is to be sure that it supports your operating system. If Mac compatibility is important for you, make sure to check the box for that support. For Windows, you may want to visit the manufacturer’s website to make sure they have a driver available for your OS…you may also get a sense from their support site how well-supported their products are on the software side.

Understanding Levels

The best microphone you can buy can still sound pretty awful if you don’t have a basic understanding of audio levels. One concept you should take the time to grasp is gain staging. The very short version is that gain staging is the process of optimizing signal levels throughout your recording chain. So for example, if you have the levels on your microphone too high, you may end up introducing unnecessary noise in your recordings. One reason you might have your mic levels too high is if you are not properly positioning yourself relative to the mic. For most mics, you want to be around 2″-6″ from the mic, because the mics ability to pick up your voice drops off quickly the further away you are. If you try to record from 2 feet away, you’ll likely need to crank the gain on your mic way up, and as a result get a ton of noise. You can use software to remove this noise later, but you’ll get far better results by properly managing the levels at the outset. Another problem of low signal levels is that if you later have to boost the signal so your voice can be heard, you’ll also be boosting any noise that was recorded.

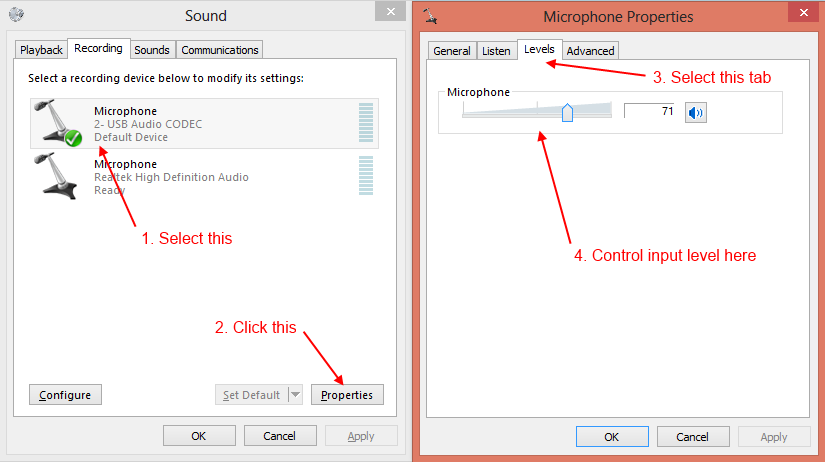

If you’re using Windows 7 or later, you can manage the input level of your USB microphone by going to the desktop, right-clicking the speaker icon in the tooltray, and selecting “Recording devices” from the pop-up menu. The resulting dialog will show all currently enabled recording devices, whether built-in (such as a laptop mic), or external. Select the item you want to manage, and click the Properties button, and then click the Levels tab to manage the input level for that mic, as shown below:

Note that some mics, including the one I use, have a built-in level adjustment, so you can tweak the levels as close to the source as possible. The goal here isn’t to set everything as loud as possible, but you may find, for example, that the default Windows setting for your mic is set too low, and as a result you end up cranking the level in your recording software, and picking up extraneous noise.

Of course, you’ll also have access to your levels in your recording software. Speaking of which, whether you use it for recording, or simply as a tool for post-production, you should probably download a copy of Audacity. Audacity is a free and open source audio editor. For the price, it can’t be beat, and provides pretty much all the functionality you could want for editing and modifying your audio. Sure, there are commercial packages that may be a little more polished, but if you’re on a budget, free is a nice price.

Location, Location, Location

It’s also worth saying that you should start with a reasonably quiet environment for recording, and be aware of the acoustic character of the room you’re recording in. If the room has bare walls and hardwood floors, you’ll likely have a good deal more natural reverb, which may or may not be what you want. A room with wall-to-wall carpet, and heavy drapes, on the other hand, will tend to absorb high-frequency sounds, making it more acoustically “dead”. You don’t necessarily need to create your own home studio, complete with acoustic foam all over the walls, to get a good sound. Simply changing your recording location to one that’s less acoustically active may make all the difference you need.

To get a sense for what a powerful difference your recording location can make, I recommend having a listen to Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks,” which features one of the best-known (and most-sampled) drum riffs in rock history. The drums were recorded with the drum kit at the bottom of a stairwell and the microphones at the top of the stairwell, providing a natural reverb that gives the track part of its characteristic sound.

The Gear I Use

OK, so enough about theory, what about practical matters like what I actually use? My gear list is pretty simple:

Microphone: Samson G-Track USB Condenser mic

The G-Track was my choice of mic for a couple of reasons. It’s a high-quality condenser microphone that’s reasonably priced (around $120 on Amazon), and has direct monitoring (so you can hear what the mic is picking up with no latency from processing) and an additional input that can be mixed right in the mic. This feature is aimed at musicians, so they can record their instrument using the same gear as their vocals, making for a very portable recording rig. For me, the appeal was the possibility of being able to plug a second mic in if I wanted to do interviews, so I’d only need one USB input. In practice, I’ve never used the mic that way, but it’s turned out to be a very good quality mic for my purposes, so I’ve seen no need to replace it.

The G-Track was my choice of mic for a couple of reasons. It’s a high-quality condenser microphone that’s reasonably priced (around $120 on Amazon), and has direct monitoring (so you can hear what the mic is picking up with no latency from processing) and an additional input that can be mixed right in the mic. This feature is aimed at musicians, so they can record their instrument using the same gear as their vocals, making for a very portable recording rig. For me, the appeal was the possibility of being able to plug a second mic in if I wanted to do interviews, so I’d only need one USB input. In practice, I’ve never used the mic that way, but it’s turned out to be a very good quality mic for my purposes, so I’ve seen no need to replace it.

I’ve got mine mounted upside-down on a boom arm (more on that below), which looks something like the picture to the right.

Shockmount: Samson SP04

While the G-Track comes with it’s own desk stand that works fine, I strongly recommend that you spend the money for a shock mount. This is a simple apparatus that isolates your mic from unwanted vibrations through the mic stand, and it’s essential if your mic is on a desk mount, because otherwise every bit of vibration of your desk (including your typing if you’re recording a screencast) will tend to be picked up by your mic.

Microphone Boom: Rode PSA1 Swivel Mount Studio Microphone Boom Arm

If you’re on a tight budget, you can get away with skipping this one, but I absolutely love having my mic mounted on a boom. This allows me to very quickly position the mic for optimal pickup, plus I can simply move the mic up and out of the way when I’m not using it, rather than having it be one more thing cluttering my desk (and given how cluttered my desk is already, that’s a big deal). It’s really simple to install, and I’ve got mine clamped to a stand I use to boost my external monitor up, so it’s mostly hidden behind my monitor. Going back to the discussion about audio levels, having your mic mounted on a boom makes it MUCH easier to put your mic where it needs to be for optimizing your input levels, as opposed to trying to position yourself relative to the mic.

The boom is spring-loaded, which is a good thing because the G-Track mic is pretty heavy.

Pop Filter

I don’t currently have one mounted, but another piece of gear I keep handy is a pop filter. It’s job is to prevent the popping sound caused by plosives (for example, when you say the letter “p” which tends to spike the audio level). Pop filters are pretty cheap, so even if you’re on a budget, you should consider picking one up. If you just can’t swing the cost, or would rather put that cash into a nicer mic, a simple technique can often do the trick…just turn your head just slightly off-axis from the mic, so that the air from the plosive goes past the mic instead of directly into it. Most mics will still pick up plenty of signal, but this can significantly reduce the pops.

Recording Audio for Video

One more quick note for those who are recording video as well as audio…in my opinion you should NEVER use the built-in mic on a camcorder or handheld (Flip or similar) video camera. As a rule, these are awful microphones, and will pick up a great deal of noise, whether you’re indoors or outdoors. Instead, consider a wireless lavalier microphone and receiver set. If your camera has an audio input, you simply plug the receiver into the camera, and the mic transmitter can be tucked in a pocket or clipped to your belt. This will give you MUCH better audio quality, because the mic will be close to your mouth, rather than across the room. My warning here is be prepared to spend a decent amount of money on this kit. I went with the cheapest option I could find, and I definitely regret it. The audio isn’t as bad as the built-in mic on my video camera, but the transmitter and receiver sometimes don’t connect properly, and the build quality is simply awful (I had to take one of the units apart to fix the battery door, which had become jammed).

Conclusion

I hope you’ve found this brief foray into the world of audio recording interesting and useful. Podcasting and screencasting can be fun and rewarding ways to share your knowledge with others, and it doesn’t have to cost a fortune to get good audio quality.

I hope you’ve found this brief foray into the world of audio recording interesting and useful. Podcasting and screencasting can be fun and rewarding ways to share your knowledge with others, and it doesn’t have to cost a fortune to get good audio quality.

With a little bit of effort, you can create podcasts and screencasts that will be a joy to listen to, and will keep your listeners tuning in over and over again. Remember that the most important tool in your audio toolbox isn’t your laptop, or your microphone, it’s your ears. So don’t just record and publish, take the time to listen to your recordings. If you’re anything like me, this will take some discipline, and will take getting used to…very few of us like the sound of our own voices. And if this part really bugs you, you might even want to recruit a friend or two to give your stuff a listen before you push the Publish button. Either way, listening is an important step in the publishing process.

If you’d like to hear what my recordings sound like, you can find many of my screencasts on my profile page on Channel 9.

With decent equipment, some practice, and good content, you’ll have happy listeners who come back for each new podcast or screencast you produce. So what are you waiting for? Get recording!

Comments

Comment by Brian Johnson on 2014-03-26 16:43:00 +0000

Great piece G. I found it through a search and had no idea you wrote it until I looked for the author name. 🙂

Comment by devhammer on 2014-03-26 16:49:00 +0000

Thanks, Brian! Glad you enjoyed it. Although I’ve moved things around a bit in my office, I’m still rocking the same mic and boom for my WintellectNOW videos.