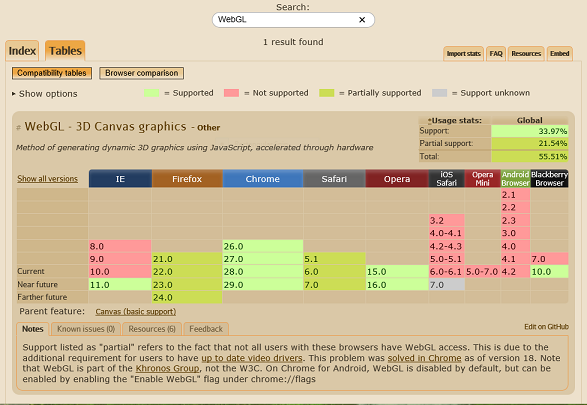

If you’ve been away for a while, you may not have heard that WebGL is supported in Internet Explorer, starting with version 11, currently available as a preview release, either as part of the Windows 8.1 preview, or as a stand-alone release for Windows 7. And I have the proof right here:

For more info, you can read the IE11 announcement here, and be sure to check out the IE Test Drive site for lots of examples of what you can do with the new version.

NOTE: At the time of this writing, IE 11 is in preview release. As such, you can expect that some things may not work perfectly, and performance is not representative of the final release.

My purpose in this post is to introduce WebGL for those, like myself, who may be new to the technology. The short version is that WebGL brings a 3D graphics API (designed to be very similar to OpenGL) to the HTML5 Canvas element. So if you’ve followed my series on getting started with HTML5 Canvas, you’re already aware that Canvas natively includes only a 2D drawing context. And while it was possible to play some tricks and get pseudo-3D in Canvas, it wasn’t real 3D. WebGL changes all that.

Now, if you’re someone who’s done any amount of 3D rendering in native code, you probably know that going from 2D to 3D can add a world of complexity, not to mention lots more code to do even simple things. So while I could try to show you a basic demo using just the WebGL APIs, that would likely be painful for both of us, so forget it. Instead, I’m going to take advantage of an available JavaScript 3D library called three.js, which provides (among other renderers) a renderer for WebGL. You can download three.js, as well as peruse the source code, on Github.

Hello, World!

Well, it wouldn’t be an introduction without a hello world example. Of course, in most languages, we use that literally, printing out the text “Hello, World!”. In other environments, that’s either not possible, or really uninteresting. For example, in the world of microcontrollers (Arduino, Netduino, etc.), hello world usually consists of flashing an LED. For our WebGL hello world, we’ll show a spinning cube.

And the three.js folks were even kind enough to include the sample code in the readme for the library. Here’s what it looks like:

1: <script>1:

2: var camera, scene, renderer;

3: var geometry, material, mesh;

4:

5: init();

6: animate();

7:

8: function init() {

9:

10: camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera( 75, window.innerWidth / window.innerHeight, 1, 10000 );

11: camera.position.z = 1000;

12:

13: scene = new THREE.Scene();

14:

15: geometry = new THREE.CubeGeometry( 200, 200, 200 );

16: material = new THREE.MeshBasicMaterial( { color: 0xff0000, wireframe: true } );

17:

18: mesh = new THREE.Mesh( geometry, material );

19: scene.add( mesh );

20:

21: renderer = new THREE.CanvasRenderer();

22: renderer.setSize( window.innerWidth, window.innerHeight );

23:

24: document.body.appendChild( renderer.domElement );

25: }

26:

27: function animate() {

28: // note: three.js includes requestAnimationFrame shim

29: requestAnimationFrame( animate );

30:

31: mesh.rotation.x += 0.01;

32: mesh.rotation.y += 0.02;

33:

34: renderer.render( scene, camera );

35: }

</script>

You can view the working example here.

The code above creates all the necessary variables for a simple 3D scene, including a camera, which it initializes and places in the scene, the scene itself (to which the other objects will be added), a 3D cube, a material with which to render the cube (in this case, a basic mesh), and a renderer. In the animate function, the cube is rotated slightly each time the function is called, and then the scene is re-rendered. Note that the three.js library automatically adds the necessary Canvas element to the DOM, with the following code:

1: document.body.appendChild( renderer.domElement );

If you’ve got sharp eyes, you may have noticed something missing in the code sample, however. The code above uses the CanvasRenderer. Instead, we want to use the WebGLRenderer, which can provide better performance. So we’d change line 21 of the code above to look like this:

1: renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer();

Once having made that change, we should be all set, with a simple Hello World style WebGL demo that will work with any browser that supports WebGL (see the chart above).

NOTE: In addition to the advantage of simplicity, another big advantage of using three.js rather than coding directly to the WebGL API is that because three.js supports other renderers, the code you write using three.js may be able to work on browsers that don’t support WebGL, albeit at a performance cost.

But Wait, There’s More!

Even cooler, for those of you building apps for Windows 8, because WinJS apps automatically get the features in Internet Explorer 11, that means that you can also use WebGL to build apps and games for Windows 8, using the same code that you’d use for the web.

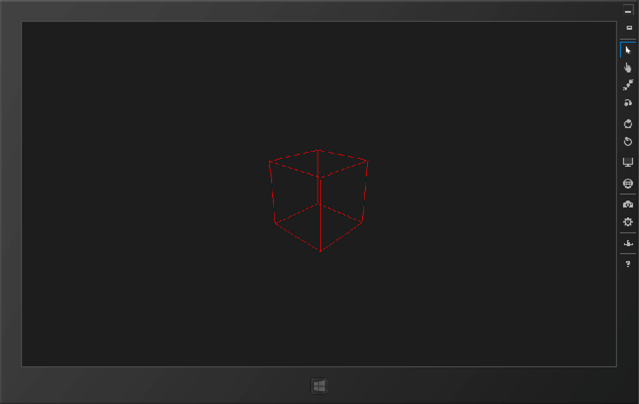

So, for example, I could fire up Visual Studio 2013 Preview, create a new Blank JavaScript Windows Store app, and plug the sample code above into the default.html file, and with a few tweaks (I modified the code to run the init function from the body element’s onload event, and bumped up the size of the cube), and in a few short minutes have the following running inside the Windows Simulator (note that the Simulator won’t give you the best performance, but it does offer the ability to test at different resolutions and orientations, as well as other useful features):

There’s lots more to play with, of course, including different types of materials, lighting, etc., and you can read about them all in the three.js documentation.

You can download the code for my Windows 8.1 implementation of the three.js cube demo, as well as another cube demo I did a couple weeks ago that includes a point light and a BasicLambertMaterial, here:

Other Libraries

While I’d definitely recommend against trying to sling WebGL code without a helper library (unless you’re a hard-core 3D guru, or a masochist), three.js isn’t the only game in town. Some colleagues of mine in DPE have been working on a framework of their own, called Babylon.js. They’re also working on an accompanying framework to simplify game development, called GameFX. Both are still works in progress, but you can try them out and keep up with the projects on these blogs:

<h2>

Summary

</h2>

<p>

It’s a great time to be a web developer. There are great client libraries for everything from DOM manipulation to game development, and powerful tools to help you develop your sites and apps. With WebGL support in IE 11, web developers can bring 3D to their sites with more confidence, and Windows app developers can leverage the same code that works on the web to build cool games and experiences for the Windows Store.

</p>